Scuba diving is one of those activities that everyone says they want to do one day, but often never get the chance to experience. If you’re reading this right now, you are one of the lucky ones attempting to put their money where their mouths are and give scuba diving a try to explore the underwater world to explore unbelievable dive sites. But before you dive into deep waters or off dive boats, we must cover the basics of what recreational scuba diving is and how you can do it.

There are many ways to describe scuba diving. Some people think of it as a sport or lifestyle while others think of it as a tourism activity or a meditative experience. In general, you may think of scuba diving as an underwater experience. At its core, scuba diving is an activity where you dive underwater to experience the beauty and nature that lie beneath the ocean.

There are various aspects and sub-branches of what scuba diving entails. However, in this article, we will keep things simple, short, and easy to follow and tell you about recreational scuba diving. We will talk about the basics you need to know about scuba diving as a beginner. So, if you are new to the world of scuba diving, keep reading so that we can dive into all you need to know to get started.

What Is Scuba Diving?

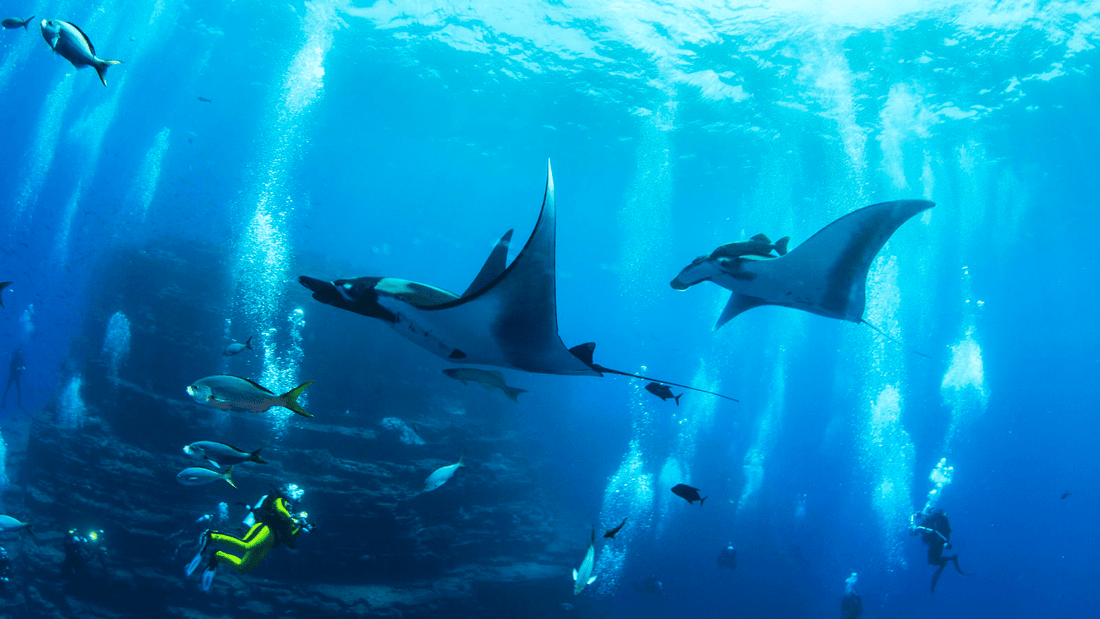

Scuba diving as a sport is when a person dives underwater to explore the ocean. There are various types of scuba diving. However, for most people, scuba diving is an activity they do recreationally as tourists while on vacation or holiday. Recreational scuba diving often is done off dive boats to experience unbelievable dive sites. Recreational divers put on a scuba tank to breathe underwater to see the beauty of the ocean and interact with sea creatures.

Scuba diving is a common hobby among people of all ages. You may have heard how some people do yoga or Zumba to de-stress. Becoming a certified diver and going Scuba diving has become another meditative activity that many general people do to destress. The experience of being weightless and “flying” through the water while watching marine life, exploring spectacular reefs, underwater caves, or even diving into sunken wrecks is something unlike anything else in this world.

Many people also progress from being recreational divers to making scuba diving a profession or lifestyle. There are multiple types of professional Scuba diving careers including becoming a dive instructor or even a marine biologist or archaeologist to help with underwater research. As of yet, 80 percent ocean around the globe is still unmapped, and becoming a professional scuba diver allows you to help advance our knowledge of the underwater world.

Is Recreational Scuba Diving Dangerous?

This is a question that a lot of people ask, and it’s a valid question. After all, you are diving into an unknown and potentially dangerous environment. But the truth is, with the proper traning and precautions, scuba diving can be a safe and enjoyable experience for everyone.

In order to answer this question, it’s important to first understand what recreational scuba diving is. Recreational scuba diving is simply diving for pleasure, rather than for occupational or scientific purposes. It’s a wonderful way to explore the world below the surface and see things that you can’t see anywhere else.

Scuba diving is an activity that is enjoyed by thousands of people around the globe each and every day and when compared to many other outdoor and sporting activities, is considered a safe and low-risk venture. Even such widespread activities as swimming, fishing, and horseback riding have higher reported fatality rates than diving.

That is why it is crucial to take a scuba diving course from a well-known training organization such as Padi. Training agencies are one significant difference between diving and most other sports and is the most significant contributor to the safety record of scuba diving. There is a direct correlation between the popularity of training agencies and the safety record of scuba diving.

Some of the biggest dangers associated with recreational scuba diving include:

- Drowning

- Decompression sickness

- Lung overexpansion

- Ear barotrauma

- Marine life hazards

There are many reasons why this may occur, such as equipment failure, faulty dive planning, or ascending too rapidly. However, in most cases, divers can avoid these issues by following safe and correct diving practices which they are taught during the certification process.

Do You Need A Certification To Scuba Dive?

Technically, it is not illegal to scuba dive without a certification. However, if you want to scuba dive safely, you will need to get certified by a scuba diving instructor. As previously mentioned. If you are recreational diving, you will need to train under an instructor. The instructor will give you lessons just like a regular class.

After the lessons, you will have to prove your knowledge by taking a test. If you pass the test, you will be certified as a beginner scuba diver. Almost every institution around the world will need you to show your license or certification before letting you dive into their premises or onto their dive boats. So, if you want to scuba dive properly, you need to have a scuba diving license.

In general, scuba diving isn’t something you can learn on your own. Even if you learn the principles of everything online, putting them to practice is a whole other issue. Thus, if you want to learn scuba diving properly, and get access to a wider territory, getting a scuba diving license is essential.

How To Get A Scuba Diving Certification?

To get a scuba diving certification, you need to enroll in a scuba diving class. Various agencies around the world offer scuba diving courses. If you complete these courses with positive results, you will receive a scuba diving certification. Some of the most popular scuba diving agencies include PADI, BSAC, SDI, NAUI, etc.

What To Expect From Scuba Diving Lessons?

What To Expect From Scuba Diving Lessons?

SAFATY REMIDERS AFTER SCUBA DIVING

1. Never hold your breath

As every good entry-level dive student knows, this is the most important rule of scuba. And for good reason — breath holding underwater can result in serious injury and even death. In accordance with Boyle’s law, the air in a diver’s lungs expands during ascent and contracts during descent. As long as the diver breathes continuously, this is not a problem because excess air can escape. But when a diver holds his breath, the air can no longer escape as it expands, and eventually, the alveoli that make up the lung walls will rupture, causing serious damage to the organ.

Injury to the lungs due to over-pressurization is known as pulmonary barotrauma. In the most extreme cases, it can cause air bubbles to escape into the chest cavity and bloodstream. Once in the bloodstream, these air bubbles can lead to an arterial gas embolism, which is often fatal. Depth changes of just a few feet are enough to cause lung-over expansion injuries. This makes holding one’s breath dangerous at all times while diving, not only when ascending. Avoiding pulmonary barotrauma is easy; simply continue to breathe at all times.

2. Practice safe ascents

Almost as important as breathing continuously is making sure to ascend slowly and safely at all times. If divers exceed a safe ascent rate, the nitrogen absorbed into the bloodstream at depth does not have time to dissolve back into solution as the pressure decreases on the way to the surface. Bubbles will form in the bloodstream, leading to decompression sickness. To avoid this, simply maintain a rate of ascent no faster than 30 feet per minute. Those diving with a computer will be warned if they are ascending too fast, while a general rule of thumb for those without a computer is to ascend no faster than their smallest bubble.

Always remember to fully deflate your BCD before starting your ascent and never, ever use your inflator button to get to the surface. Use the acronym taught to new divers to explain a five-point ascent: Signal, Time, Elevate, Look, Ascend (STELA). Unless worsening surface conditions, diminished air supply or any other serious mitigating factors make it unsafe to do so, always perform your 3-minute safety stop at 15 feet, which provides a barrier of conservatism that significantly decreases your chances of decompression sickness. A recent paper on diving fatalities that combined research from the Diver’s Alert Network (DAN) in the U.S. and Australia and BSAC in the U.K. showed that an uncontrolled ascent was the precipitating factor in 26 percent of the fatalities analyzed.

3. Check your gear

Underwater, your survival depends upon your equipment. Don’t be lazy when it comes to checking your gear before a dive. Conduct your buddy-check thoroughly —if your or your buddy’s equipment malfunctions it could cause a life-threatening situation for you both. Make sure that you know how to use your gear. The majority of equipment-related accidents occur not because the equipment breaks but because of diver uncertainty as to how it works.

Make sure you know exactly how your integrated weights release and how to deploy your DSMB safely, and that you know where all the dump valves are on your BCD. If you are preparing for an unusual dive, make doubly sure that you’ve made all the appropriate equipment arrangements; for example, when getting ready for a night dive, do you have a primary torch, a backup and a chemical light? Are they all charged fully? If prepping for a nitrox dive, have you made sure to calibrate your computer to your new air mix? Being sufficiently prepared is the key to safe diving.

4. Dive within your limits

Above all, remember that diving should be fun. Never put yourself in an uncomfortable situation. If you aren’t physically or mentally capable of a dive, call it. It’s easy to succumb to peer pressure, but you must always decide for yourself whether to dive. Don’t be afraid to cancel a dive or change a location if you feel that the conditions are unsafe that day. The same site may be within your capabilities one day and not the next, depending on fluctuations in surface conditions, temperature and current. Never attempt a dive that is beyond your qualification level — wreck penetrations, deep dives, diving in overhead environments and diving with enriched air all require specific training.

5. Stay physically fit

Diving is deceptively physically demanding; although much of our time underwater is relaxing, long surface swims, diving in strong current, carrying gear and exposure to extreme weather all combine to make diving a strenuous activity. Maintaining an acceptable level of personal fitness is key to diving safely. Lack of fitness leads to overexertion, which can in turn lead to faster air consumption, panic and any number of resulting accidents.

Obesity, alcohol and tobacco use and tiredness all increase an individual’s susceptibility to decompression sickness, while 25 percent of diver deaths are caused by pre-existing diseases that should have excluded the person from diving in the first place. Always be honest on medical questionnaires and seek the advice of a physician as to whether or not you can dive. Be mindful of temporary impediments to physical fitness — while a cold may not be dangerous on land, it can cause serious damage underwater. Recover fully from any illness or surgery before getting back in the water.

6. Plan your dive; dive your plan

Taking the time to properly plan your dive is an important part of ensuring your safety underwater. No matter who you’re diving with, make sure that you have agreed on a maximum time and depth before submerging. Be aware of emergency and lost-diver procedures. These may differ slightly from place to place and depend upon the specifics of the dive. If you are diving without a guide, make sure you know how you’ll navigate the site beforehand. Make sure you’re equipped to find your way back to your exit point.

Communicate with your buddy, making sure that you are both agreed on the hand signals you will use; often, we’re paired with strangers while diving and signals can differ quite drastically depending on a diver’s origin. For example, the signal used for ½-tank of air in Asia and the Caribbean is the same signal used by divers in Africa to call the end of a dive. Sticking to your plan is as important as original planning. Check your gauges frequently throughout the dive. It’s easy to lose track of time, and suddenly find yourself dangerously low on air or several minutes into decompression. According to the diver fatality statistics provided by DAN, insufficient gas supply was the leading cause of fatal emergency ascents for the deaths analyzed, which could easily have been avoided if air supply had been properly monitored.